DIVE: Trump asks SCOTUS for anti-gay discrimination

He's not just transphobic. He's homophobic too.

This is an experimental supplement to your regular Fording the River Styx experience, a bonus issue of the newsletter beyond the daily round-ups that drills down on one specific topic. Please let me know if you would appreciate receiving more content like this and feel free to share any other feedback you’d like to provide.

The Trump administration is trying to undermine all LGBTQ nondiscrimination protections. Last week, we saw the Department of Justice’s attack on trans employment protections, and this week we’re going to look at its attack on lesbian, gay, and bisexual rights.

There are three Title VII cases heading to the Supreme Court this fall. Last week, I explained to you the Harris Funeral Homes case, which asks whether it’s legal to fire someone for their gender identity. If you haven’t read that explainer, give it a glance, because a lot of the same questions, precedents, and arguments are relevant in these other two cases.

The other two cases involve someone being fired for being gay. Zarda v. Altitude Express, Inc. is about Donald Zarda, who was fired from his skydiving job in 2010. When a woman was uncomfortable jumping tandem with him, he informed her that he was gay, which prompted her boyfriend to complain and the company to fire him. Both a district court in New York and the full Second Circuit Court of Appeals agreed (10-3) — despite the Trump administration arguing otherwise in 2017 — that the firing was illegal discrimination under Title VII. Zarda subsequently died in a base jumping accident, but his estate continues to fight the case.

The other case went the other way. In Bostock v. Clayton County Board of Commissioners, Gerald Lynn Boston was a Court Appointed Special Advocates director. He claims he was subjected to homophobic slurs and eventually fired for being gay — all of which only transpired after his employer found out he had joined a gay softball team. The county has claimed instead that he was fired for mismanaging funds, but it never filed charges against him. The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed Bostock’s claims, saying Title VII did not entitle him to protection on the basis of sexual orientation. (You might recall that it was the same court that previously did the very opposite, protecting transgender people in Glenn v. Brumby.)

With this split between circuit courts, the Supreme Court is now tasked with determining whether Title VII protects sexual orientation. If it doesn’t, there will be no way for LGB people to seek relief for discrimination under federal law.

Past precedent

As I noted last week, the Supreme Court has previously expanded the definition of “sex” under Title VII in two cases. In Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989), SCOTUS determined that “sex stereotyping” constitutes sex discrimination. And in Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services (1998), SCOTUS extended sexual harassment protections to same-sex sexual harassment, specifically noting that Title VII could be interpreted beyond what Congress originally intended.

There have been many sexual orientation discrimination cases throughout the years, and appellate courts had ruled that “sex” does not encompass “sexual orientation,” binding the hands of district courts with those precedents. That started to crumble a bit, however, after the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) reversed its position in 2015 (a few years after it recognized transgender protections in Mia Macy’s case).

In a case called David Baldwin v. Dep’t of Transportation, the EEOC reasoned that sexual orientation discrimination against the complainant “relied on sex-based considerations and took his sex into account in its employment decision.” The agency concluded that “sexual orientation is inherently a ‘sex-based consideration,’” and thus protected under Title VII.

A few years later, in a case called Hively v. Ivy Tech Community College, an appeals court followed suit, reversing its earlier precedent.

Kimberly Hively sued the school where she worked part-time in Indiana, claiming it had denied her a promotion because of her sexual orientation. She had even been reprimanded, she alleged, for kissing her girlfriend goodbye in the school parking lot. Though the district court dismissed her complaint, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to revisit their past rulings and reconsider whether the discrimination was illegal. After hearing the case en banc (before all the judges), an 8-3 majority agreed in 2017 that the discrimination was illegal under Title VII, undoing the precedent that had prevented judges from interpreting the law that way.

That same year, the Eleventh Circuit ruled the other way in a similar case (Evans v. Georgia Regional Hospital) that preceded Bostock, but curiously, the Supreme Court did not elect to take up appeals that year to resolve the dispute — perhaps because Ivy Tech did not fight the ruling against it.

So we now have two courts that say anti-gay discrimination is illegal under federal law, and one court that contemporaneously says it isn’t. What are the arguments in these cases?

Why “sex” = “sexual orientation”

Before we get to the Trump administration’s arguments, here’s a quick tour of the three main arguments in favor of protecting gay, lesbian, and bi people under Title VII.

The first argument in favor of protecting people on the basis of sexual orientation under Title VII is very similar to the arguments in the trans discrimination case: sex stereotyping under the Price Waterhouse precedent.

Arguably, one of the most fundamental stereotypes about sex is the expectation that people pair with the opposite sex. It’s likewise no coincidence that stereotypes about being "gay” are often associated with being effeminate and weak, while stereotypes about being “lesbian” are often associated with being butch and aggressive. It’s hard to argue that firing a man for being gay is somehow not related to your expectation for how men should behave as men.

There are two other compelling ways to consider the role “sex” plays in sexual orientation discrimination. These can be a little tricky to conceptualize, especially when compared to one another, so I’ve made some goofy little visual aids to assist.

The first of these two arguments is that anti-gay discrimination discerns between the sex of employees’ partners. Imagine all of the men in a workplace. If the employer fires male workers who have relationships with other men, but doesn’t fire male workers who partner with women, the employer is necessarily making a distinction on the basis of sex. It’s the sex of the partner, but it’s still based on sex. Here’s a visual:

The only difference between the men on the left and the men on the right is the sex of their partners. So treating the men on the left differently is discrimination “because of sex.”

In 2016, a federal judge ruled in favor of a plaintiff alleging anti-gay discrimination, and while her ruling was based on sex stereotyping, she also made note of this reasoning by juxtaposing it with race. Title VII’s race protections have been used to protect an employee who was treated differently because they in a personal relationship with a person of a different race. If it’s racial discrimination to mistreat an employee on the basis of their partner’s race, then it’s sexual discrimination to mistreat an employee on the basis of their partner’s sex.

Now let’s flip it around, and this requires slightly rethinking how we usually conceive of “orientation.” Because queer people are a minority, we instinctively distinguish between “different-sex” (straight/bi) and “same-sex” (gay/bi) to suss out those who defy societal expectations. But if you take the person’s own gender out of the equation, we’re just talking about orientations toward men and/or women. In a sense, you could argue that a gay man and a straight woman have the same orientation toward men.

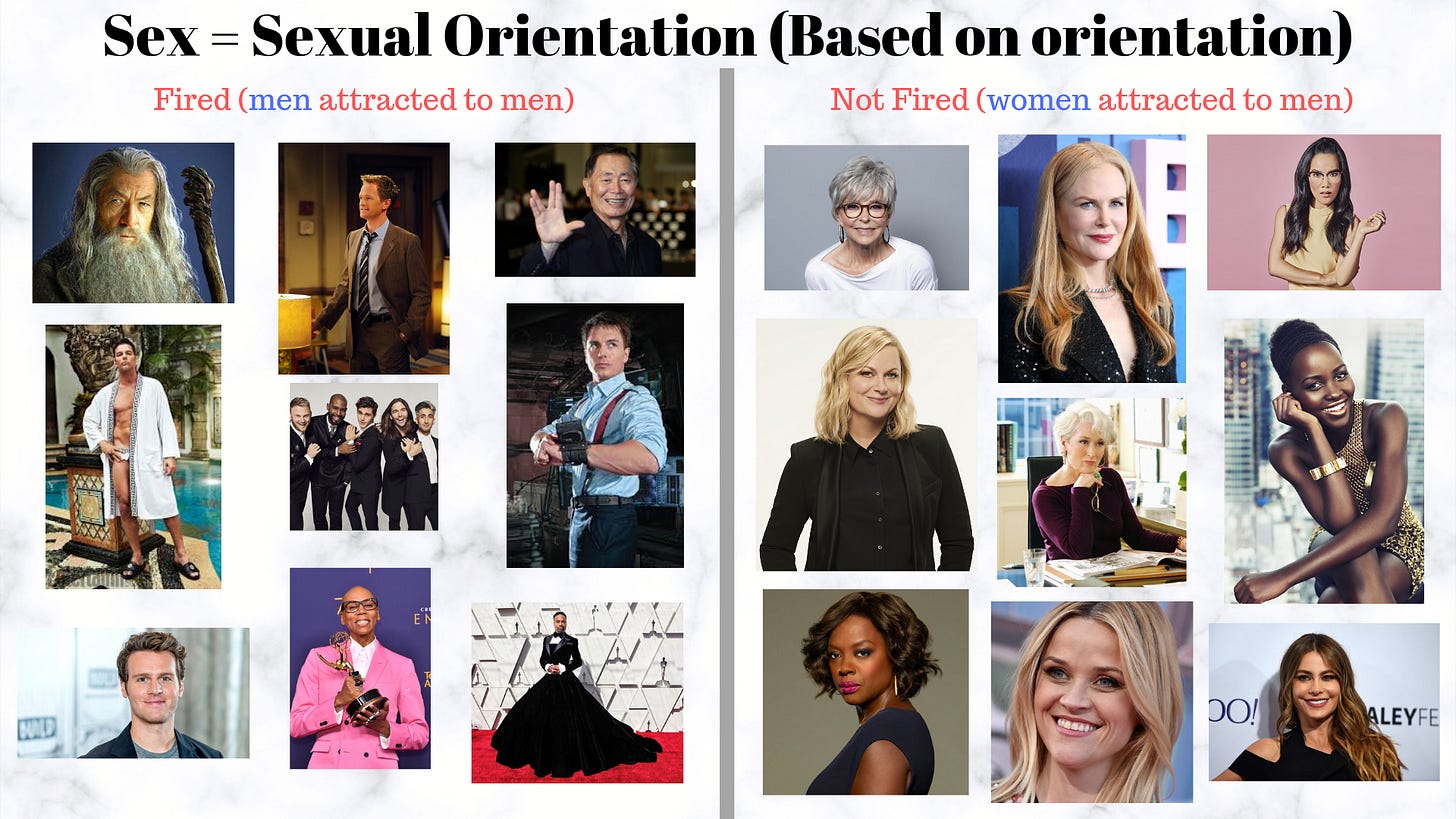

And that’s what the other argument does, thereby revealing that sexual orientation discriminates against one sex that has a certain orientation to a particular sex. So now imagine all of the people in an office who have a sexual orientation toward men. If an employer is only discriminating against the men who are sexually oriented toward men, and not the women, then the employer is making a clear distinction on the basis of sex. Here’s what that looks like:

As you can see, all of these employees have a sexual orientation toward men, but only the men are suffering for it. And this specifically is the argument that convinced the Seventh Circuit (Hively) and subsequently Second Circuit (Zarda) to conclude that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is discrimination “because of sex.”

You might hear this sometimes described as the “but for” argument. If Hively had been a straight man instead of a lesbian woman, she would not have been denied a promotion; thus, she would not have been denied a promotion “but for her sex.”

And as the Second Circuit pointed out in Zarda, this reasoning would likewise apply to Ann Hopkins, the plaintiff in SCOTUS’s Price Waterhouse “sex stereotyping” case. She was denied a partnership because she wasn’t womanly enough in her presentation and demeanor. But if she’d been a man and acted that way, she wouldn’t have experienced discrimination. Thus, she would have gotten that partnership “but for her sex”; in her case, it was just a different set of stereotypes that she was compared against.

As you can see, all three of these arguments (sex stereotyping, partner’s sex, and “but for”) are a bit different, but can easily overlap and intersect.

For Zarda and Bostock, it all comes down to interpretation. Do you compare straight people to gay people and call that a separate category that isn’t protected, or do you recognize that sexual orientation is really just a proxy for discrimination that accounts for sex?

Guess which way the Trump administration went…

The Trump brief

The Trump DOJ brief insists that it’s legal to fire people for being gay, but it requires some bizarre contortions to do it. It relies on a few of the same arguments we saw last week as well, so let’s knock those out of the way first before getting to the confusing part. Warning: It’s confusing because it’s dumb.

Like in the Harris Funeral Homes brief, the DOJ cites dictionaries from 1964 to point out that “sex” only means “biological sex” and not sexual orientation. It also likewise points out that because Congress has tried to pass “sexual orientation” protections separately, that proves that the two are not connected (ignoring the possibility it was an attempt at clarification in the wake of courts concluding otherwise).

The DOJ also once again tries to dismantle the “sex stereotyping” protections from the Price Waterhouse case. They continue to insist that sex stereotyping only counts as discrimination if it’s evidence of unequal treatment against all men or all women in a workplace.

Remember from above the two different interpretations? Are we comparing “gay men and gay women” or are we comparing “men-oriented men and men-oriented women”? Well, the Trump DOJ insists it must be the former — that sexual orientation is a separate category, and so long as an employer is treating all gay people the same “regardless” of their sex, then no sex discrimination is taking place.

Why not compare men and women who are both oriented toward men? The DOJ says that’s an unfair comparison, because it requires changing both the gender (man to woman) and the orientation (gay to straight). In a sense, their argument boils down entirely to this arbitrary interpretation that orientation can only be defined along the axes of “same-sex vs. different-sex” and not “men vs. women.”

But why isn’t that still sex stereotyping discrimination? And here’s where the administration really tries to have its cake and eat it too. This is also where it gets confusing, so stick with me because I’m going to reframe it a couple different ways to help you make sense of this very petty argument.

The DOJ argues that sexual orientation, as a separate category of identity, simply doesn’t intersect with sex stereotypes. Here’s what the brief actually says to delineate sex stereotyping:

…[H]iring only “masculine” men and “feminine” women would violate Title VII not because it relies on stereotypes per se, but because it treats effeminate men worse than effeminate women — and likewise masculine women worse than masculine men.

Huh? What we have hear is a disagreement as to what the apples are and what the oranges are.

When it comes to orientation, the DOJ wants to compare gay men and women without considering their gender (i.e., treat all gay people the same). But when it comes to mannerisms, they take the exact opposite approach, associating those mannerism with the respective gender (i.e., treat all masculine or feminine people the same).

If the DOJ really wanted to be consistent, they’d apply sex stereotypes the same way they do sexual orientation — by grouping the non-conforming people together. So if all gay people have to be grouped together (gay men and lesbian women), all gender non-conforming people (effeminate men and masculine women) should be grouped together. But they don’t do that. They want to have it both ways just so it excludes gay people from consideration under the law.

Confusing, I know. Here’s another way the brief tries to justify the double standard, in which you can see an attempt to simultaneously uphold Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins while undermining its “sex stereotyping” conclusions:

…[A]n employer who “fires both a woman like Hopkins for being too ‘macho’ and a man for not being sufficiently ‘manly’” does not violate Title VII because of a freestanding ban on stereotypes. Rather, the employer violates Title VII because it would be treating a subset of women (macho women) worse than a similarly situated subset of men (macho men) and — in a separate act of discrimination — treating a subset of men (effeminate men) worse than a similarly situated subset of women (effeminate women). Each practice separately violates Title VII because each results in “disparate treatment of men and women.” By contrast, sexual-orientation discrimination, standing alone, does not result in any subset of either sex being treated worse than a similarly situated subset of the opposite sex.

To paraphrase it yet another way, the DOJ is just arbitrarily asserting that gay people can not be singled out for sex stereotyping, but gender non-conforming people can.

This makes a bit more sense when you see how the DOJ is argues that gay people can be be protected from sex stereotyping — just not because they’re gay! They would have to prove the sex stereotyping separate from their orientation. For example, an effeminate gay man might have a Title VII case under this logic if he could show that his employer “would not fire masculine gay men.” (Yes, it actually says that.)

As far as the Trump DOJ is concerned, firing gay men and gay women is fine, but firing effeminate men and masculine women is not. That’s the line they’ve drawn, and it makes no reasonable sense — unless your only motive is allowing discrimination against gay people.

A couple of other things from the brief are worth noting. The specter of bathrooms is once again raised to suggest that protecting LGB people would go too far. “After all, a man would never be prohibited from using the women’s bathroom if he were a woman,” the brief quips of the Second Circuit’s logic. It’s a slippery slope argument that isn’t relevant to the facts of the case. The lines we draw around sex are arbitrary, and adjusting them to more fairly accommodate queer people does not require erasing them entirely.

In its argument that discriminating based on sexual orientation isn’t necessarily sex stereotyping, the DOJ additionally pointed out that “an employer may be relying on reasons that have nothing to do with gender norms, such as moral or religious beliefs about sexual, marital, and familial relationships.” The notion that anti-gay discrimination is somehow not a gender-norm stereotype simply because it’s couched in a religious belief is not compelling — but it could be incredibly dangerous if five Supreme Court justices buy into it anyway.

Conspicuously, the DOJ put out a public statement defending this brief, but made no such public comment about its anti-trans brief last week. The statement offers zero consideration for how the department’s interpretation impacts LGB people:

Combined, this brief and the brief in the funeral home case make an argument that all LGBTQ people should be erased from protection under federal employment law. The reasoning behind this motive requires factually rejecting the very nature of what it means to be non-heterosexual or non-cisgender in arbitrary and capricious ways just to justify discrimination against the queer community. It may read as wonky, legal jargon, but it’s anti-LGBTQ bigotry through and through.

If the Supreme Court agrees with the Trump administration in this trio of cases, the only way to protect queer people from employment discrimination under federal law will be to pass the Equality Act, which adds sexual orientation and gender identity to the Civil Rights Act. Fewer than half the states currently offer comprehensive LGBTQ protections at the state level, meaning workers in the rest of the country will have no protection whatsoever.

Moreover, it’s clear from these arguments that the Trump DOJ is fine with weakening even the “sex stereotype” precedents that help protect men and women from discrimination even when they aren’t queer. Losses in these cases won’t only hurt queer people, but all of society.

If you enjoyed this bonus issue of Fording The River Styx, I hope you’ll consider signing up so that you never miss any issues of the newsletter. I also welcome your feedback.

(White House protest photo credit: Flickr/Ted Eytan.)